Mapping the wetland genome: a team effort across the UK

Wetlands are more than habitats - they're living libraries of biodiversity. Thanks to a remarkable collaboration with the Darwin Tree of Life project and the Wellcome Sanger Institute, we're helping write the genomic story of the UK's wetland species.

Darwin once wrote:

…from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Studying the evolution of species today involves studying all their DNA – called a genome. To study all 70,000 species in Britain and Ireland, an impressive team effort has joined together. That team effort, called the Darwin Tree of Life project, includes WWT, the Natural History Museum and the Sanger Institute.

Sanger Institute Professor, Mark Blaxter, who leads the Darwin Tree of Life project, explains:

A genome is like a time machine – it allows scientists to study how species adapt and respond to climate and environment over time.

How is a genome studied?

DNA from the frontlines of wildlife health

A genome starts with a sample. The most important WWT contribution to the Darwin Tree of Life project is tissue samples from wetland species that stem from our wildlife health surveillance programme — a vital part of the GB Wildlife Health Partnership. This programme spans all our managed wetland reserves in the UK and plays a key role in understanding species health. Through post-mortem examinations and disease monitoring, we not only identify causes of death and assess wider impacts but also gain the opportunity to collect crucial tissue samples that enable genomic research.

Living collections that make a difference

Our living collections - featuring waterfowl, amphibians and small mammals - also offer access to high-quality blood and tissue samples. These samples are carefully collected during routine health checks or taken from deceased individuals. These are particularly important for representing rare and elusive wetland species in the UK's genomic archive, helping preserve their genetic legacy for generations to come.

The Sanger Institute celebrated the genome release of the smew (Mergellus albellus), as the 3000th species they've sequenced.

Male smew duck

Professor Mark Blaxter explains:

The smew is a striking duck that spends its summers on the taiga in northern Europe and Russia, and visits estuaries and wetlands here in the UK every winter. While globally the smew is doing well, here in the UK it is on the conservation red list because of its reliance on threatened wetlands ecosystems. Having this genome can now help ongoing conservation efforts led by WWT.

Collaboration is at the heart of it all

This work is only possible thanks to brilliant teamwork, not just across organisations but within WWT itself. Reserve wardens and aviculturists at our sites are the unsung heroes, collecting specimens and ensuring they make their way to WWT Slimbridge, where Veterinary and Wildlife Health Officers Michelle and Rosa carefully identify, process and prepare samples for the next steps on the genomic journey.

Whether it’s collecting samples on-site or during visits to other reserves, it’s a joined-up effort. And thanks to our field and aviculturist colleagues, specimens reach us ready to be transformed into valuable genomic data that partners at the Natural History Museum, and the Sanger Institute take forward to get one step closer to a fully pieced together genome puzzle.

DNA samples laboratory

What happens when a WWT sample reaches the Natural History Museum?

From saltmarsh to museum

The Natural History Museum has maintained the UK's most comprehensive database of taxonomy and nomenclature for over a decade.

This database provides key biological recording systems – and is referred to when tracking samples from WWT to the Darwin Tree of Life project partners. WWT samples are prepared by Michelle and Rosa, the sample is then shipped to the Darwin Tree of Life Sampling Coordinator at the Natural History Museum, Inez Januszczak. Inez lets Michelle and Rosa know what samples are needed for the Darwin Tree of Life project and if there is a sample sent that already has a genome, it is kept at the Natural History Museum in their Biobank for future scientific use. Sometimes, leftover materials from select species are also passed on to the expert Natural History Museum curators.

Frozen test tubes - species sample management

Dive into the laboratory

Once the WWT specimens have finished their time at the Natural History Museum, these are sent to the Sanger Institute where the team are ready to prepare samples for DNA extraction, genome sequencing, and experts assemble these genomes for researchers around the world to use.

Sanger Institute laboratory staff, Amy Denton, trained as a veterinarian but was always drawn to research in the laboratory. Amy extracts DNA from all sorts of taxa - such as bird, small mammal and frog samples. As genomes are all as different as the species they represent, the methods used are constantly being updated and improved. Amy remembers one WWT sample - the elegant tundra swan, was particularly tricky.

High-quality DNA for each WWT sample is extracted by a well-established process, developed by the Sanger Institute. Once Amy has extracted DNA, the samples are checked and sent for DNA sequencing. This allows experts to see the entire genetic code of an organism, and they can now piece the puzzle together, which is known as assembling the genome. Once this genome has been finished, it is released into an accessible database, for anyone to use.

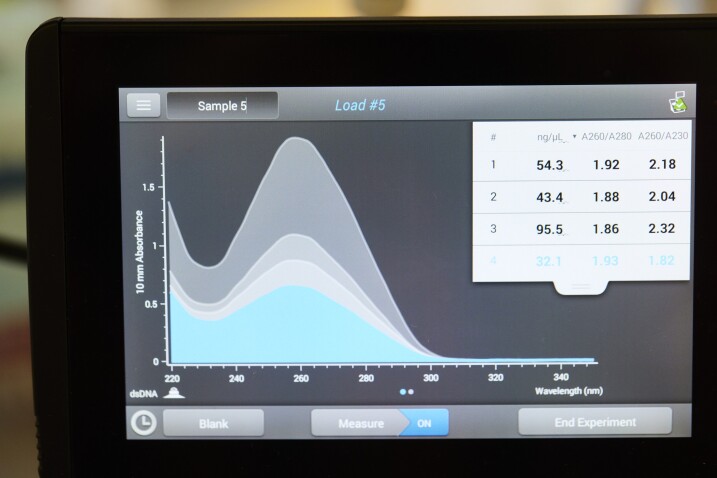

Graphs showing DNA concentration

Why do genomes matter?

Every genome produced from WWT samples contributes to unlocking the secrets of our wetland wildlife - supporting future conservation and giving researchers a clearer picture of the UK’s ecological web. It's about understanding where species come from, what pressures they face, and how we can better protect them.

WWT Veterinary and Wildlife Health Officer, Michelle O'Brien, explained:

This has been an inspirational project to be involved in and has provided fascinating insights into the genomes of both the wild and collection species we work with on a daily basis.

WWT Conservation Veterinary Officer, Rosa Lopez, added:

In today's constantly shifting epidemiological landscape, this kind of knowledge helps to better support health planning for conservation work, whether it's species recovery projects or translocations.

We’re starting to unlock the secrets of wetland genomes – thanks to the hard work of teams across WWT and our partners. Here’s to science powered by feathers, fur and a whole lot of fieldwork.