Tough Birds, Fragile Homes. International Flamingo Day 2022

International Flamingo Day (IFD) occurs each year on 26th April. It is a day set up by the IUCN Flamingo Specialist Group (FSG) to celebrate the six amazing species of flamingo and their wonderful wetland homes. Of these six species, four are of conservation importance (three - the Chilean, puna and lesser flamingos - are near threatened and one - the Andean flamingo - is vulnerable to extinction). The wetlands that flamingo live within are not commonly found habitats and occur in only a select few places around the world. These wetlands can be some of the most challenging of environments for animals to live in.

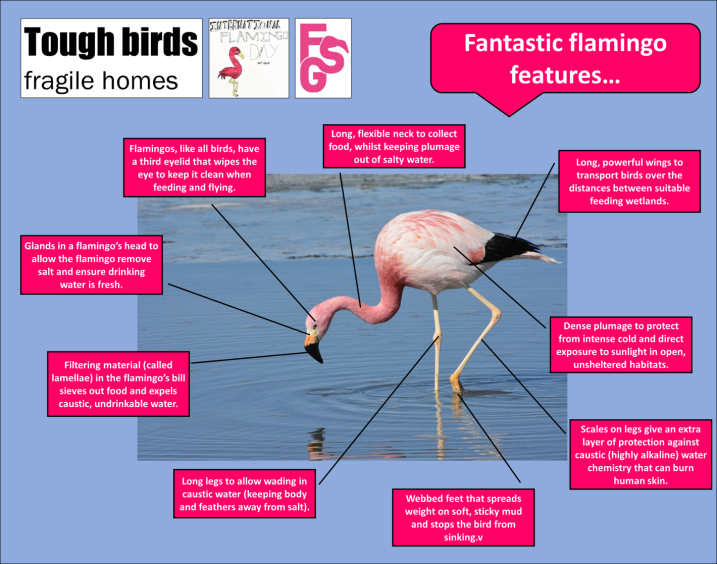

The theme of IFD this year is Tough Birds, Fragile Homes, to identify and explain the unique adaptations of the birds themselves and the characteristics of the amazing wetlands that they live within. Flamingos have very specific needs when it comes to suitable habitats, and these habitats vary in characteristics depending on where in the world they are found and the species of flamingo that uses them.

- They like wide, open spaces that allow many birds to feed together but to still have enough room for individual flamingos to be distanced from each other. They like their friends but they need their own space too!

- They like to be undisturbed but will be found in areas around human dwellings and activities if these habitats are good feeding patches.

- They try to avoid competition with other species, but they can be found in wetlands that are full of biodiversity (for example Lake Nakuru in Kenya).

- They can favour wetlands that are remote and inaccessible, but these wetlands can contain valuable resources that humans wish to extract.

- They can occur at the tops of mountains or at sea level.

- They can be freezing cold water or water at near to boiling point.

- These wetlands are generally salty or have a very alkaline (caustic) pH.

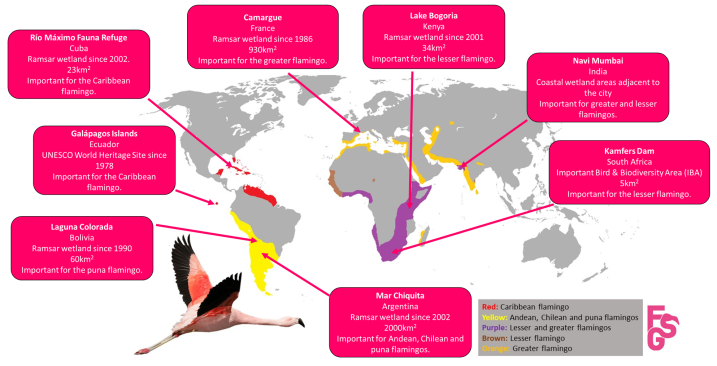

You can see some examples of wetlands that flamingos are found in in the illustration below.

Some species of flamingo, such as the Andean, Chilean and puna (James’s) flamingo are found at high elevations in the salt flats and soda lakes of the Andes Mountains. These birds can range up to elevations of 4500m during the breeding season.

Caribbean flamingo and greater flamingo are birds of lowland wetlands, and especially coastal regions. This can put them into conflict with development and human activities that are changing coastlines and reclaiming wetlands areas.

The lesser flamingo is perhaps the most specialised in its habitat requirements. Aside from a small population in India, this is a bird renown for its love of the East African soda lakes where it wades around in water that can be up to pH 10.5 (very highly alkaline). The lesser flamingo selects these caustic water bodies as they are full of microscopic plant and algae materials (called cyanobacteria) that it feeds upon and gains its bright pink and red plumage colours. The habitat specialism of the lesser flamingo puts it very strongly at risk from human and climatic disturbance to these wetlands as it has little other options to move to if they disappear or become degraded (and not useful for the birds).

You can see the characteristics of different flamingo wetlands, and images of what these wetlands look like in the illustration below.

The high Andes flamingos are also at risk of declining populations if their habitat changes. Mining for lithium, an element found in the volcanic soils of the flamingo’s wetlands, degrades the habitat and reduces water level. The batteries of electronic devices, such as tablets and mobile phone, contain lithium and therefore the greater the need to extract, then the more harm to the birds.

These high mountain flamingos are pressured by climatic change to. As temperatures warm and weather patterns become more instable, the seasonal cycles of flooding that flamingos rely on to create the best conditions for breeding become more unreliable. Changes to water levels and the amount of permanent water also impacts on feeding areas and therefore squeezes the available habitat that flamingos use for finding something to eat.

So whilst these wetlands might sound tough, they are actually fragile because of their specific water chemistry or climatic conditions or wider environment that they are found within. It is is the flamingo that is tough to have evolved to survive and thrive within them.

Flamingos, in biological terms, can be considered extremophiles. That means a species of animal adapted to extreme conditions where few other species are capable of living. Flamingos have evolved for these niches to avoid competition for feeding and nesting areas. Their complex way of feeding and their need to all nest at the same time restricts where flamingos are able to live.

You can see the different adaptations (features that flamingos have evolved) for these extreme wetlands in the diagram below.

Being extremophiles means that flamingos can cope with exposure to direct sunlight and high levels of UV, as well as extreme heat and extreme cold. Some species, such as the Andean and puna flamingos, have to survive when the water in their mountain lakes freezes. Flamingos can travel for long distances between suitable areas for feeding and breeding- but this strategy only works when there are a number of safe havens that they can rely on moving between.

Other species of wetland animal that live alongside of the flamingos in their inhospitable wetlands can also be considered extremophiles, for example some species of cichlid (a type of fish) that have evolved to live in the East African soda lakes. You can see a short video of these fish below (they are not as brightly coloured as the flamingos!).

So when you're on your next visit to one of the WWT centres that house flamingos (Slimbridge, Martin Mere, Llanelli and Washington) see if you can spot some of the unique adaptations that flamingos have to their extreme yet fragile wetland homes. Thank you for your support of WWT and your support of the conservation work of these amazing creatures and the incredible habitats they rely on.