How wetlands can help us and wildlife in hot weather

Every time a heatwave hits, our wetlands become inundated with people and wildlife. Find out more about how wetlands help wildlife deal with extreme hot weather, and how we look after them on our reserves.

As temperatures soar, the draw of water becomes overwhelming. Every time a heatwave hits, our coasts, lakes and inland waterways become inundated with visitors as we seek out any little bit of ‘cooling blue’ that’ll offer some respite from the sweltering heat.

And we’re not alone. In hot weather, our wildlife seeks out damp, cool, watery places too. As well as providing vital water for animals to drink, these wetlands also store and filter water and provide food in the form of plants, fish and insects.

Wetlands: a traveller’s delight

Wetlands like desert oases provide essential refuge for migrating birds. As they journey south to overwinter in the warmer climes of Africa, they face a perilous desert crossing – the Sahara. This vast wilderness of sand, rock and gravel is one of the hottest and driest places on earth. For the 500 million birds that migrate south, it presents one of their biggest challenges as they fly thousands of miles to reach countries like Senegal, The Gambia and South Africa.

Some, like the cuckoo cross this inhospitable place in one 50 to 60 hour continuous flight, covering a distance of around 3,000 miles, others avoid it altogether, flying down the coast, feeding at estuaries along the way. But for others, the desert oasis offers a vital place to touch down, refuel and rest during the intense midday heat.

In the dry season, on the plains and savannahs of Africa, watering holes become magnets for wildlife, as birds and other animals flock to them to drink, eat and cool down with a quick dip.

In short, wetlands are vital for people and wildlife in hot, dry weather. And with experts warning that climate change will lead to more extreme weather events, including hotter, drier summers, wetlands are only going to become more important.

In urban areas like Colombo in Sri Lanka, where temperatures can rise to forty degrees, it’s estimated the city’s wetlands can lower the temperature by 10 degrees, with this effect extending up to 100m away from the water.

No water, no life

Water is vital for life and when it disappears, life disappears with it. Lower water levels also mean increased water temperatures. This in turn leads to changes in oxygen levels - there is less dissolved oxygen in warmer water than in colder water. All of which affects our aquatic wildlife, so reducing the availability of food for our waders and birds like kingfishers that rely on invertebrates to feed the fish they eat.

In the wetlands of Cambodia, experts predict it’s going to get hotter and drier, with fears this could affect the iconic sarus crane. Their main food source is the water chestnut and there are concerns increased periods of drought and hotter, drier wet seasons may reduce its availability, making the sarus crane highly vulnerable to climate change. WWT is working hard to provide greater water security for people and wildlife in the region.

Conversely in the UK, heatwaves often result in pond water levels falling to the extent that ponds can dry out entirely, with unexpected benefits for our aquatic wildlife. Llanelli’s Reserve Manager, Brian Briggs explains:

On the reserve a recent amphibian survey showed a strong negative correlation between the presence of fish in a pond and the presence of amphibians, clearly demonstrating the importance of fish-free ponds for amphibians.

So, while the drying out of ponds is obviously damaging to pond life in the short term, it can really benefit amphibians through the loss of local fish populations.

Changing temperatures; changing behaviour

Dry weather brings its own challenges for the wildlife on our reserves. Unlike humans, birds don’t have sweat glands to help them regulate their temperature, so they have to rely on behavioural change to help them cool down. At Steart we often see breeding birds shielding their young from the intense heat under their wings. And if the wet mud, in areas like the saline lagoons starts to dry out, we can see them move their young to different areas of the reserve altogether.

Sunbathing ducks

Many ducks, geese and swans will ‘sunbathe’ sitting down on the ground and opening their wings out. This helps them keep cool as they radiate heat away from their body by convection in the breeze that blows over them.

Other birds like herons and storks take this ‘wind catching’ behaviour to the extreme, often contorting themselves into strange ‘yoga style poses’ to cool down.

Preventing a hot pink flamingo

Flamingos however are well adapted to extreme environments. In fact they time their breeding cycle to coincide with hot weather as these are better conditions for them to raise their chicks in. It’s usually really hot and sunny at the lakes and saline lagoons where they live in the wild with little in the way of shade or shelter, so they have evolved to cope with high temperatures and direct sunshine. They’re so tough we call them extremeophiles - organisms that have adapted to live in conditions where it looks impossible for life to be sustained.

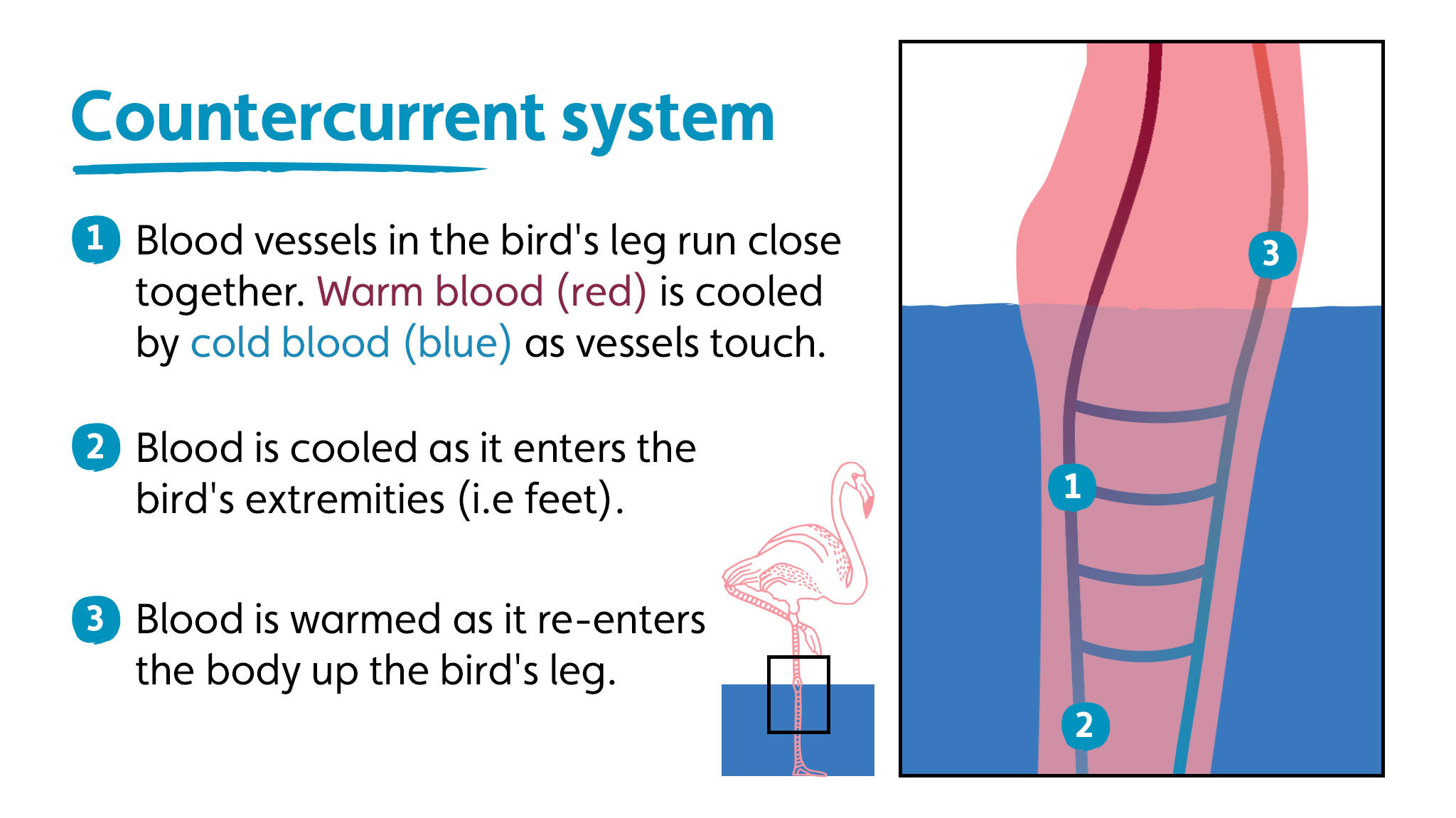

One way they manage the heat is with the help of the countercurrent system in their legs, which helps them by cooling their blood, something they have in common with a lot of waterbirds.

But flamingos still need access to clean water for bathing so they can regulate their own temperature when it gets hot. Clean and well-maintained plumage allows them to reflect the heat. For them to remain happy, our number one priority in the summer is to keep the water clean and flowing in their enclosures.

Just add water

When it’s hot and dry, the careful managing of water around our reserves becomes key. While our wetlands are a valuable source of water when rainfall is low, acting as sponges to slowly release moisture, sometimes in extra dry weather we need to give them a helping hand. As our Site Manager at Steart, Alys Laver explains:

We are able to bring in additional water with the use of tilting weirs and stop log structures. We also have telemetry that enables us to monitor levels remotely and very accurately.

At London Wetland Centre, dry weather brings with it the risk of fire to our dry grassland meadows and we have to pump on a lot more water. Insects that rely on the meadows for nectar sources and reproduction can suffer a great deal in a heatwave if the grasses dry out too much.

At Llanelli if a heatwave occurs during the spring we try to hold water onsite and maintain the soft muddy wetland margins needed by feeding lapwing chicks.

Building resilience to manage extremes

One important way we help our sites deal with higher temperatures is by promoting diversity. More species gives you greater scope to deal with extremes in temperatures; where some species may struggle, others will thrive. During the drought in 2019 our wetland wildflower meadows at Steart, which are brimming with a huge variety of grasses and flowers, yielded much better yields of hay compared to the mono-cultures of rye grass that stopped growing in the hot weather.

We also use traditional breeds of cattle to graze our wetlands as they’re more adaptable and resilient to harsh conditions. But in a heatwave we do need to take extra care of our livestock as Llanelli’s Reserve Manager, Brian Briggs explains:

We need to ensure they have access to shade from the sun (especially our Shetland sheep), drinking water and a mineral lick to replace salt and minerals lost through sweating. In extended periods of dry weather, the vegetation growth slows down and we may need to adjust livestock numbers or even supplementary feed the animals.

The threat of invasive species

The rapid growth of invasive species like crassula helmsii or New Zealand pygmyweed is another challenge for our reserves teams during hot weather. At Llanelli, in heatwaves it can form thick mats over the surfaces of ditches and shallows and so we need to increase our invasive species checks and control work.

What can I do?

All wildlife needs water and the best way to make your garden wildlife friendly during a heat wave is to add water. Even a small pond can make a difference. It’s also a good idea to leave undisturbed areas of shade, keep your plants well watered and put out extra food and water for birds and other animals – harvested rainwater is best.

With hot weather comes water shortages. But we can all do our bit to reduce their impact. WWT is calling for changes in the law to incentivise better water management and behaviour change. And small changes can make a big difference. If each adult in England and Wales turned off the tap when brushing their teeth we’d save enough water for nearly 500,000 homes every day or enough to fill 180 Olympic swimming pools.

Visit wetlands

You can get closer to nature and enjoy being by water at any of our wetland centres. To help keep everyone safe at the moment we’ve made a few changes to our sites, and are asking everyone to book in advance, so we can give you the best possible day out.

Find your nearest centre