Hot pink flamingos? Flamingo care in warm weather

We've seen some mini heatwaves across the UK lately and the warm weather brings new challenges for the living collections teams at WWT centres and how they care for their animals. In this flamingo blog, let's take a quick look at how the flamingos are managed in the summertime to ensure they don't turn a really hot pink.

Lesser and greater flamingos in their natural habitat in the Rift Valley in Tanzania (above). Wide open spaces, shallow soda lakes whose caustic waters are filled with the algae and crustaceans that these birds thrive on. And look on the land! These wetlands are found in incredibly biodiverse regions of the world!

Flamingos are well adapted to extreme environments. They naturally occur in very specialised wetlands that are either incredibly salty or incredibly alkaline in pH. The lakes and saline lagoons that flamingos are generally found in occur in tropical and temperate parts of the world, where the weather can get very hot and sunny. These wetlands offer little in the way of shade or shelter and so the flamingos are exposed to the full effects of the prevailing weather conditions and temperatures. This means that the pink birds have to be tough to withstand some very harsh conditions. Even though species that live at high altitudes, like the Andean and James's flamingos, fact extremes of temperature change and dazzling levels of UV light. So bright sunshine is something flamingos have evolved to cope with.

This Andean flamingo (above) is filtering for algae and microscopic aquatic plant material, just like it would in the wild. Andean flamingos occur in high altitude saline lagoons where the harsh water conditions favour the growth of algae that turns their feathers pink. As these lagoons are really exposed, they cope well with bright sunlight.

Some flamingo species, like the lesser flamingo, flounce around in the East African soda lakes where the water pH is over 10 (that's very alkaline- so alkaline it will severely burn human skin), where the lakes are fed by volcanic hot springs (near boiling temperature water) and the normal water temperature of the lake is around 40 to 60 degrees C. Adding on to that is the fact that these flamingos are gathering at these inhospitable wetlands to feed on blooms of poisonous blue-green algae, you get the picture that the flamingo is a very tough cookie. So tough in fact that we can call them extremeophiles. Organisms adapted to living in conditions where it looks impossible for life to be sustained.

A bathing lesser flamingo (above) at WWT Slimbridge. Lesser flamingos spend a lot of time preening their feathers; in the wild this is an evolutionary adaptation to keeping their plumage free from salt crystals that form on their feathers because of the caustic soda that is dissolved in the lakes they live in. To remove these crystals, lesser flamingos have to bath in hot springs that contain fresher (but near boiling!) water around the edges of the lake. They clearly don't mind a prolonged spell in the hot tub!

Let's translate this ecological information (i.e. what we know about the birds in the wild) in the care of captive flamingos, like those you can see at WWT Slimbridge, WWT Llanelli, WWT Martin Mere and WWT Washington.

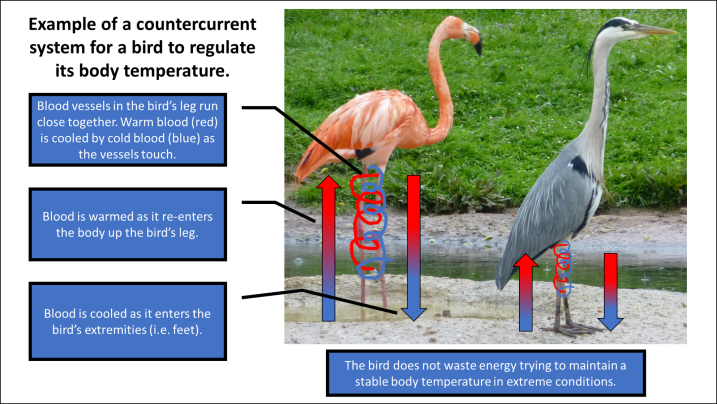

Flamingos cope with the heat and direct sunshine. So long as they have access to clean water for bathing, they can regulate their own temperature when it gets hot. In the wild, you will see flamingos standing out in the open, not phased, in the middle of the day baking in the midday sun. Clean and well maintained plumage allows flamingos to reflect the heat of direct sunlight and the countercurrent system in their legs (blood flow from and to the body exchanges heat) allows the birds to regulate a consistent body temperature by cooling their blood. So priority number 1 in the summer, for the living collections team, is to keep the water flowing between the bird's enclosures. Lots of waterbirds have a countercurrent system in their legs, ducks, geese, storks, cranes, herons, as well as flamingos, and you can see how this works in the diagram below.

The photo below will show you some of the behaviours that you can look out in warmer weather, when flamingos are keeping themselves cool. Remember, in the wild they don't have shade in the habitats they exist in, so they rely on behavioural mechanisms to cool down.

Lesser flamingos (above photo) on a warm day. Birds will sit on their "haunches" (the bird with ring code LFV) or stand on one leg (ring code LHA) and rest or sleep. If it's super hot, then flamingos will sit down. Especially in the zoo environment where they feel safe and are protected from predators, but also in the wild too when they can sit and rest on islands in the middle of a wetland.

Mr James in the classic one leg flamingo pose. Why? Of all of the theories, the most credible (and most relevant to flamingos in hot weather) is that it saves energy. In fact, a flamingo on one leg can be more stable, when resting, than a flamingo on two legs. A bird locks its leg muscles in place so that it uses no energy to remain upright. This is important in hot weather when the bird does not want to expend energy on balance as this energy expenditure will warm it up.

Flowing water contains more oxygen and therefore is healthier and can support more underwater life. This means the natural systems present in a wetland ecosystem- bacteria, algae, plants, insects, fish- all work together to keep the water fresh and clean. Which is great news for all of the birds in the living collections. They can preen and bathe naturally, maintaining excellent feather condition and keeping themselves relaxed in the hot weather.

All of that water management makes for very pretty pink flamingos. These lesser flamingos (above) produce deep red plumes in the breeding season. You can judge the health of a bird by the quality of its feathers, and these are excellent.

Flamingos benefit from direct sunlight. It stimulates their courtship display and breeding activity. So the next key job for the living collections team in summer is to ensure that plants don't get to high and that lawns are mowed to remain short. Flamingos like to out in the open for their key breeding behaviours- lots of room for marching and their famous dances as well as for nest building. Just check out the nesting colony of greater flamingos at WWT Slimbridge. They build their nests exactly like wild flamingos do, crushed together out in an area of open ground.

Nesting greater flamingos (above) at WWT Slimbridge in 2015. The birds all nest together in one area of their island, out in the open and surrounded by water. A very natural way for flamingos to breed. As a colonial (group living) species, flamingos will always nest with many other birds.

A final job to get the flamingos ready for summer is to manage the nesting and loafing (that means resting and standing) areas for the birds. A flamingo's day works on a relatively simple schedule. They feed and forage in the morning and in the afternoon and evening. They bath in the morning or afternoon and they snooze around lunch time (unless they are nesting, in which case they can be more active throughout all times of the day). They will stand around and preen for a large proportion of the day, as I mentioned previously. Therefore, flamingos need to have comfy areas to do this loafing and preening in. So the living collections team, every spring and summer, manage the islands in the bird's enclosures. Shovelling in tonnes of sand to keep flamingos comfy. This is special sand that is free draining and keeps the birds feet healthy.

That's a lot of sand! An essential part of summer flamingo husbandry is managing the areas that the birds stand and nest in. That means a lot of hard work in moving around special estuary sand, which is best for keeping chicks clean and dry and for making sure the feet of adult birds remain healthy (photo above).

All of what I have said is beautifully illustrated in this photo below. You can see the island in the Andean flamingo enclosure has been sanded and is nice and clean and fresh, and the birds have built nests. The flamingos are all bright pink and have a beautiful feather condition. You can see that the vegetation has been trimmed and managed to give the birds space to display and loaf around. And you can see the water is clean and clear. These management techniques have not only benefited the flamingos- look at the displaying pair of rosybill pochards (the two ducks at the front of the photograph). Clearly very happy to be living in this enclosure :-)