60 years of flamingos at WWT

This year, 2021, is a special year for the flamingos (and the people that love and look after them) at WWT as it marks the 60th anniversary of these ever-popular members of the living collections being cared for by WWT. Back in 1961, three pioneer groups of three species arrived at WWT Slimbridge, and now WWT has the most complete collection of this type of bird to be seen anywhere in the world.

The first flamingo species to arrive at WWT Slimbridge was imported in 1961 at the request of WWT’s founder, Sir Peter Scott, and these were 12 Chileans flamingos. These birds were followed shortly after by 13 greater and nine lesser flamingos in that same year. Today, flamingos of all six species can be seen across four WWT centres. Flocks of flamingos were first established at WWT Martin Mere in 1976 (the centre opened in 1974), at WWT Washington in 1986 (the centre opened in 1975) and at WWT Llanelli at its opening in 1991.

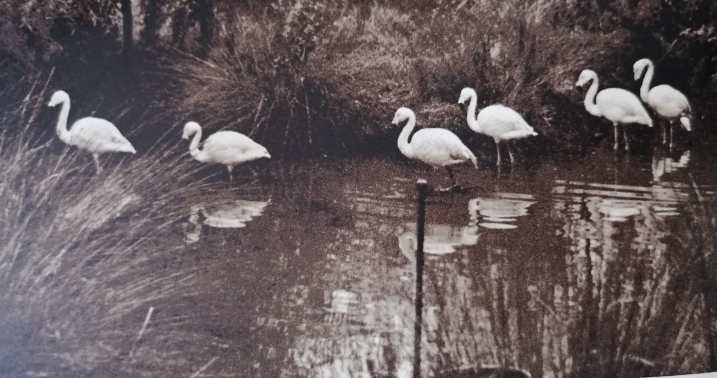

WWT's very first flamingos (photo taken from the 13th Annual Report of The Wildfowl Trust). A small flock of Chilean flamingos that quickly become one of the largest groups of these birds to be ever seen outside of their home range.

Caribbean flamingos arrived in 1962 and in 1965 the first examples of the rare and relatively unknown Andean and James’s flamingos. By 1965, Slimbridge housed well over 100 flamingos, including a huge flock (for the time) of 58 Chilean flamingos. The most flamingos ever kept in one place in the UK.

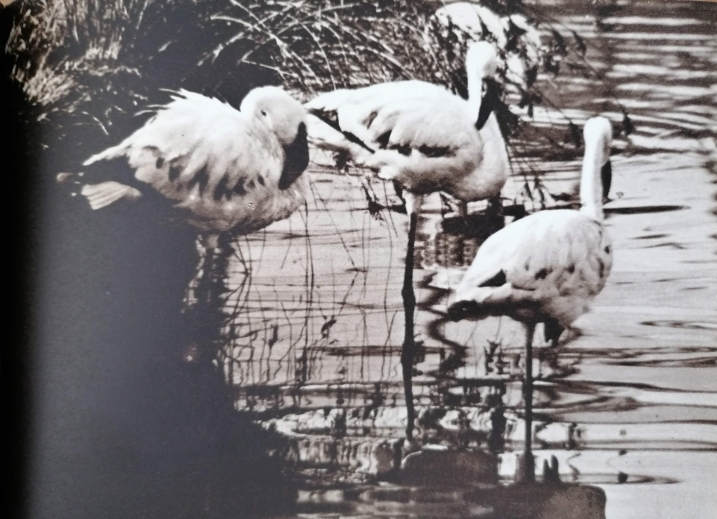

Greater and lesser flamingos soon followed the Chilean flamingos. These are WWT's first greater flamingos. Photo taken from the 13th Annual Report of The Wildfowl Trust.

And WWT's pioneering lesser flamingos. Pictured having settled into their enclosure after being relocated to the Slimbridge Wildfowl Trust. Photo taken from the 13th Annual Report of The Wildfowl Trust.

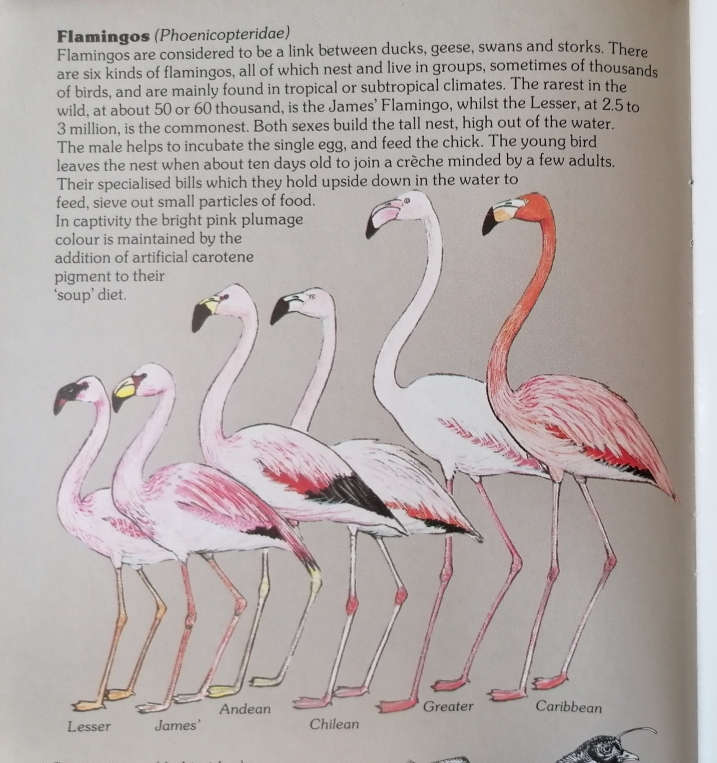

Sir Peter Scott was a keen ornithologist and he was interested in the evolutionary relationships (i.e. the family tree of different species of birds and which species are most closely related to whom) of the different species of birds that he wished to exhibit in his wildfowl collection. Peter Scott did research into the flamingos and the wildfowl and he concluded that the flamingos, based on their webbed feet, way of life, affinity to water and calls they made, were very similar to the ducks, geese and swans. And so he needed to exhibit them at Slimbridge to give the fullest picture to his visitors of what the wildfowl are and how they have evolved.

Sir Peter Scott wanted to display all six kinds of flamingo because of their (thought at the time) evolutionary links to the ducks, geese and swans. This image, taken from the 1987 Slimbridge guidebook shows his drawing of the birds and explains why he wanted to have them in his collections.

Whilst we now know that flamingos are not that closely related to ducks, we still have them at WWT because of the amazing stories they tell of the unique wetlands that they make their homes, and how vividly they can promote wetlands and wetland wildlife to WWT’s visitors (just as Peter Scott hoped for). You can still spot the close relatives of flamingos on your next visit to WWT… and in fact in your back garden. Grebes are the wetland birds closely related to flamingos. And the other are the pigeons (believe it or not!).

How the Chilean flamingo flock had grown! Do you recognise the South American Pen? This photo, from 1965 looks remarkably similar to the enclosure that these birds still live in today. I love the fact that the birds in this photo are, for the most part, still living their lives at WWT Slimbridge. Photo taken from the 1965-1966 Annual Report of The Wildfowl Trust.

Flamingos are long-lived birds and because of the good care they received, you can still see some of these original, pioneer flamingos at WWT on your next visit. Many of the lesser flamingos and Chilean flamingos are from 1961, and our special group of 19 greater flamingos that date from 1956 are still going strong in Flamingo Lagoon. Generally (in the breeding season), the pinkest and brightest birds are likely to be some of the oldest as carotenoid (what provides their pink colour) accumulates within the flamingo over its lifetime. Check for bright legs and bright beaks- these are parts of the flamingo that generally remain brightest all year around. Size counts as well; the tallest of tall males, for examples, are likely to be some of the oldest birds.

Spot some of our oldest birds. Here are greater flamingos GPS and HLH, two males from 1956!

And this is HPI, a female from 1956. Alive and well in the 21st Century.

Sir Peter Scott was passionate about flamingo conservation. He recognised the unique features of these birds, such as how they collect their food and the importance of their beautiful courtship dances, and why that made them vulnerable to environmental changes and human disturbances (way before many others had the same thoughts). He also knew that living collections and zoological organisations had a strong role to play in conserving flamingos. Building sustainable flocks in safe places that people could come and enjoy, and that researchers could study and help better understand the needs of the flamingo in the wild (what should be protected and why?). As a result of this conservation focus, Peter Scott organised the first international flamingo symposium, held at WWT Slimbridge, in 1973. The output from this symposium was published in a book “The flamingos” in 1975 that is still considered an authority text on these birds to this day. More output from this symposium was increased collaboration in the zoological community to build bigger flocks to hope that breeding of all species would become more common. For example, London and Copenhagen Zoos swapped their handful of James’s and Andean flamingos into the Slimbridge flock, and in exchange Slimbridge provided London Zoo with Chilean flamingos to increase the size of the group in Regent’s Park. Cooperation for conservation at the heart of WWT’s mission, then and now.

The WWT Slimbridge Chilean flamingos in June 2021. Some of these birds will be the 1961 originals. And they are still very much "in the pink"!

This conservation focus has also allowed WWT to build flocks of birds at its different centres without needing to take flamingos from the wild. Greater flamingos were first sent from Slimbridge to start a new flock at WWT Martin Mere in the 1980s. All of these were WWT-hatched birds. More recently, when WWT Llanelli opened it doors to the public, the beautiful Caribbean flamingo flock at the centre are also all Slimbridge-hatched birds.

Over these past 60 years of flamingo care, WWT has seen numerous “firsts” in flamingo keeping and breeding. Including, the first UK breeding of Caribbean flamingos in 1968 (and potentially of the very first flamingo chicks ever to be reared in the UK), followed by the first UK breeding of Chilean flamingos in 1969 and, in that same year, the first time that Andean flamingo had successfully nested in a zoological collection anywhere in the world.

WWT's first ever flamingo chick! These Caribbean flamingos still live in (what was called) the Orchard Pen at WWT Slimbridge. Photo taken from the 1969 Annual Report of The Wildfowl Trust.

Back to 2021, and flamingos are still at the heart of what WWT is all about. They are one of the most popular of animals to see at the wetland centres that house them and WWT is the home of the IUCN Flamingo Specialist Group, the international body that coordinates flamingo conservation and management around the world. With three species (Chilean, James’s and lesser) listed as Near Threatened and the Andean flamingo listed as Vulnerable on the global Red List of threatened species in need of conservation action, this flamingo focus is as important today as it was 60 year ago.

The WWT Slimbridge lesser flamingos in June 2021. These birds are some of our longest standing residents at WWT and this flocks is made up of many of the first flamingos to be ever housed by WWT.

I will leave you with some of my own photos, taken when I was a child on family visits to Slimbridge back in the late '80s, so you can get a sense of the flamingo history that WWT is full of. Enjoy!

The Andean flamingos got the free-run of the South American Pen, with the small flock of James's flamingos and the Chilean flamingos at the end of the '80s/start of the '90s. This scene was repeated from 2008 to 2013 when, once again, the Andean flamingo lived in "South America". The original idea behind this multi-bird mix was to encourage breeding of the James's flamingos by recreating a larger mixed species flock that this species is known to breed in in the wild. Sadly, it was not successful.

Spot the six James's flamingos! One is just peeking in on the left. Back before Mr James was our celebrity bird, there was a small flock of this unusual flamingo that lived in the Andean Flamingo Pen. Peter Scott imported James's flamingos several times in the 1960s, and donations of birds from other zoos from the 1970s to the 1980s was performed to try and encourage breeding. We now know that this lovely flamingo is best conserved out in the wilds of the Andes Mountains.

A glimpse inside the Caribbean Flamingo House. There used to be a viewing platform, at the far end of the house, that allowed visitors to observe the birds when they were housed indoors. Here you can see a mixture of young birds (grey plumage) and white birds (parents of that year). Clearly indicating a successful breeding season!

Several young Chilean flamingos in the old Lesser Flamingo House. This would be in the part of the Grounds now occupied by the "Back from the Brink" exhibit (that houses the water voles and harvest mice). The lesser flamingos would spend the summer in the main African Pen (now Flamingo Lagoon) and their house could then be used as a nursery space. The greater flamingos lived in what is now the current Lesser Flamingo Pen.

And another view of the South American Pen, which the huge colony of Chilean flamingos. The birds are nesting in the long island that is in the centre of their pond. This island is still present but has been left to become filled with wetland plants, with the flamingos now nesting on the bank at the back of their pen. If you look to the left you can see some of the old concrete nests mounds that used to be built to encourage the flamingos to breed in a specific area (you can also see that this didn't necessarily work!). We now know that flamingos are best encouraged to nest by providing a safe and secure environment with lots of clean, dry sand and some wet mud, all ready for them to construct their nests.