Data Dive - February

Take a look at what a typical February brings to our reserve with our second Data Dive

Whether rain, shine or blizzard, our reserve team do a daily count of the wild animals on our site.

In these monthly blogs, we look at that data from years gone by and explore trends, observations and records, and talk about how we manage the site and how it impacts those animals.

This month we explore the data from two frequent February visitors - the oystercatcher and the goldeneye - and also find out the best place, statistically, to go on Valentine’s Day for a romantic birdwatching date.

While frequently the coldest month of the year, especially around our coastlines here in the United Kingdom, February also brings warmth with Valentine’s Day and brief glimpses of spring approaching.

During this month, while wrapped up against the weather, we occasionally see our early spring visitors arriving, such as the avocet.

February can also be the departure time for some over-wintering migratory birds we often see flying overhead during the colder months. Pink-footed geese were last seen flying over in February in both 2022 and 2023, as well as the whooper swan, which we spotted last February before they left. This makes February potentially the last month to catch a glimpse of them as they make their journey north (until autumn at least).

The oystercatcher is a wader native to the United Kingdom, although their numbers get boosted with winter migrants coming from Norway and Iceland. Often found on tidal flats searching for their favourite foods such as cockles, mussels and worms, these striking black and white birds can be seen in gigantic flocks, sometimes in the thousands, during winter.

Interestingly, oystercatchers learn a trade from their parents, and their bill will change shape depending on their role. Some are adept at prying open shellfish with a chisel-shaped bill. Others take a more brute force approach and will hammer open shells with a blunt-ended bill. Perhaps the easiest trade for oystercatchers to master gives them a tweezer-like bill to probe for worms and small invertebrates in the ground.

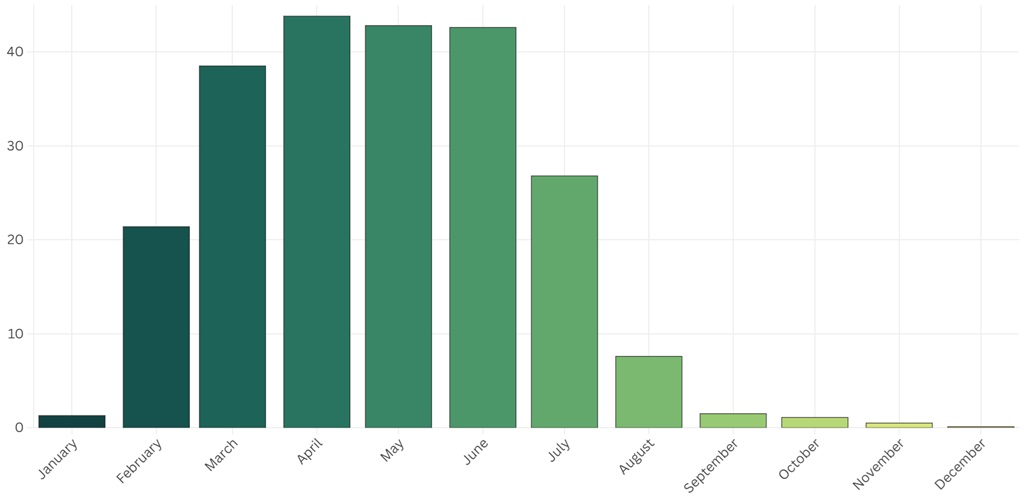

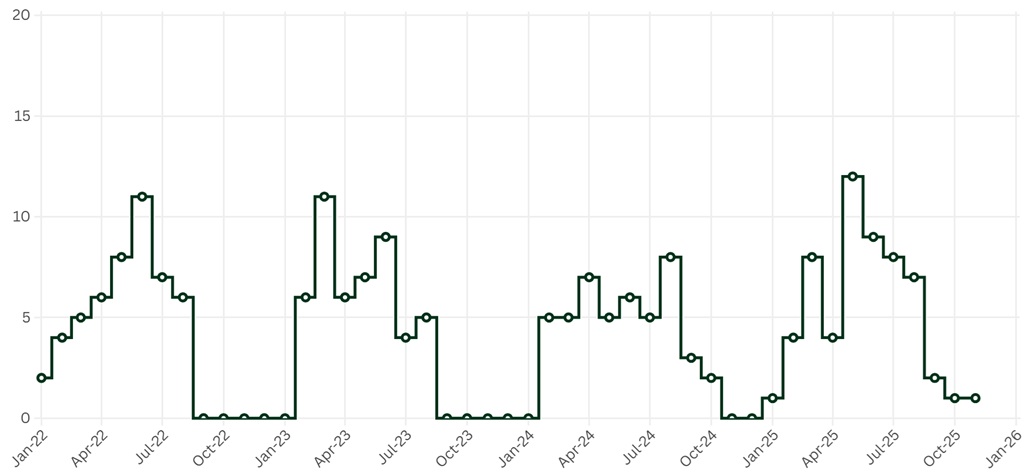

Here at WWT Washington, we start to see oystercatchers arrive around February, as they begin to move away from their gregarious winter communes and look for nesting and breeding sites. If we look at the chart below - which shows the average frequency of sightings per month across the last 10 years - we can see the oystercatcher begin to arrive in force during February, steadily building numbers into spring.

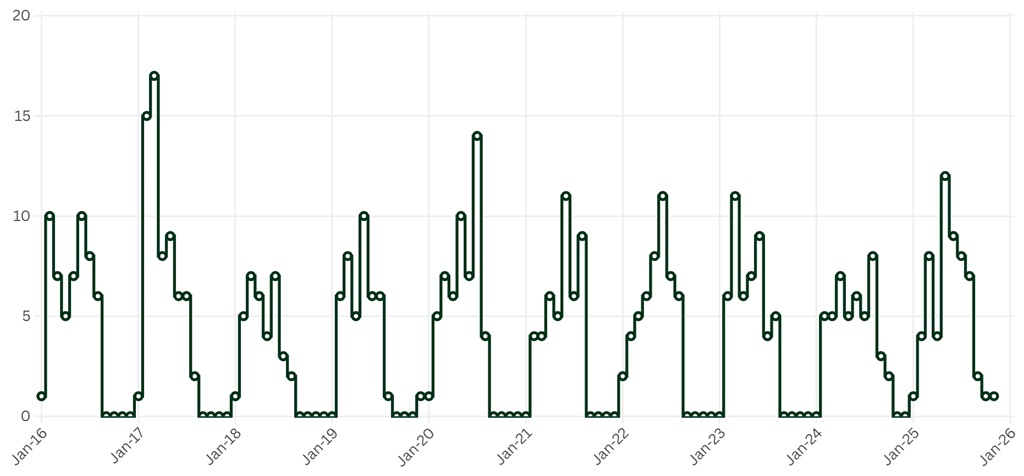

We can also see that there are a few instances where oystercatcher are recorded through the winter and when we examine the graph below, which shows peak counts across the last 10 years, we can see this is a relatively new trend.

In fact, in the last 10 years we had no oystercatchers recorded in September, October and November until 2024, when we recorded them on 4 days in September and 6 days in October. Then last year, they were recorded 11 days in September and 5 days in both October and November. This is more noticeable if we zoom in on the last few years.

On the graph above, we see that September to January in both 2022 and 2023 had zero recorded oystercatcher (oystercatcher have been recorded in both December and January previously). But then in 2024, that winter trough is now less defined with only November and December without sightings, and last year in 2025 we saw a similar pattern but now November also had records.

It’s easy to guess and make suggestions as to why this is happening. Maybe our climate is becoming more agreeable to the oystercatcher so they don’t feel the need to leave as soon after summer or maybe it was just a few birds stopping to rest while travelling to their winter commune. With such little data it’s difficult to determine whether this is a just a curious coincidence or the start of a new trend. Either way it will be interesting to revisit our autumn oystercatcher in a few years and see what new information the data brings.

Another winter visitor which seems to favour February is the goldeneye, a small duck that, while technically a resident in the UK all year round, prefers the colder temperatures of Scotland and only during the winter do we get migratory goldeneye coming across from Scandinavia. In fact, there are only a few small areas of Scotland where the goldeneye breed during spring, mostly being around the lochs, rivers and glens of Aberdeenshire, Perthshire and Inverness-shire. Outside of Scotland there has only been a handful of recorded nests in Avon and Northumberland.

The goldeneye breeding population in the UK has grown considerably over the last 50 years, from single figure breeding pairs recorded around 1970 to more than 200 breeding pairs today. Our winter population is decreasing however, despite the global population remaining stable. This is most likely due to birds not having to migrate as far in winter due to increasingly more temperate climates across Scandinavia and Northern Europe.

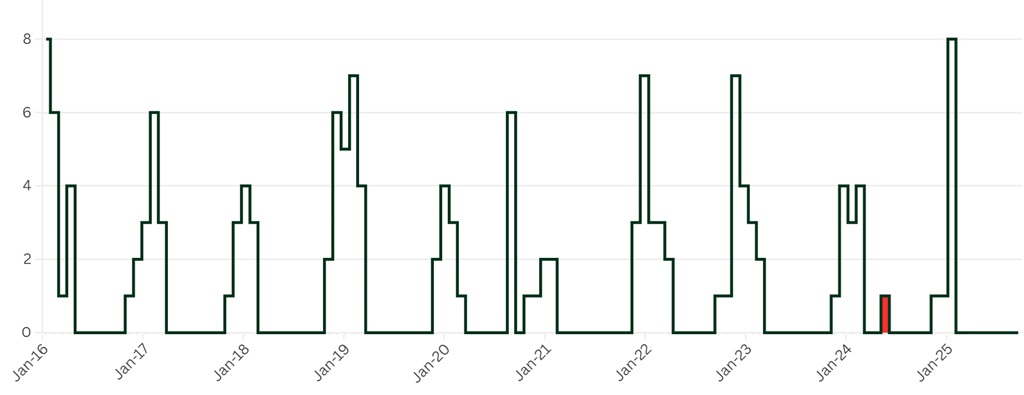

While not quite as prolific here as other places in the UK, the graph below highlights that we have consistent visitors during the winter. With a peak of 8 being sighted at once in both February last year and January 2016. An interesting occurrence however is the small hump in the middle of 2024 (highlighted red on the graph) where a lone goldeneye was spotted on the river in June - perhaps one of the rare Northumberland nesters having a day out at Washington!

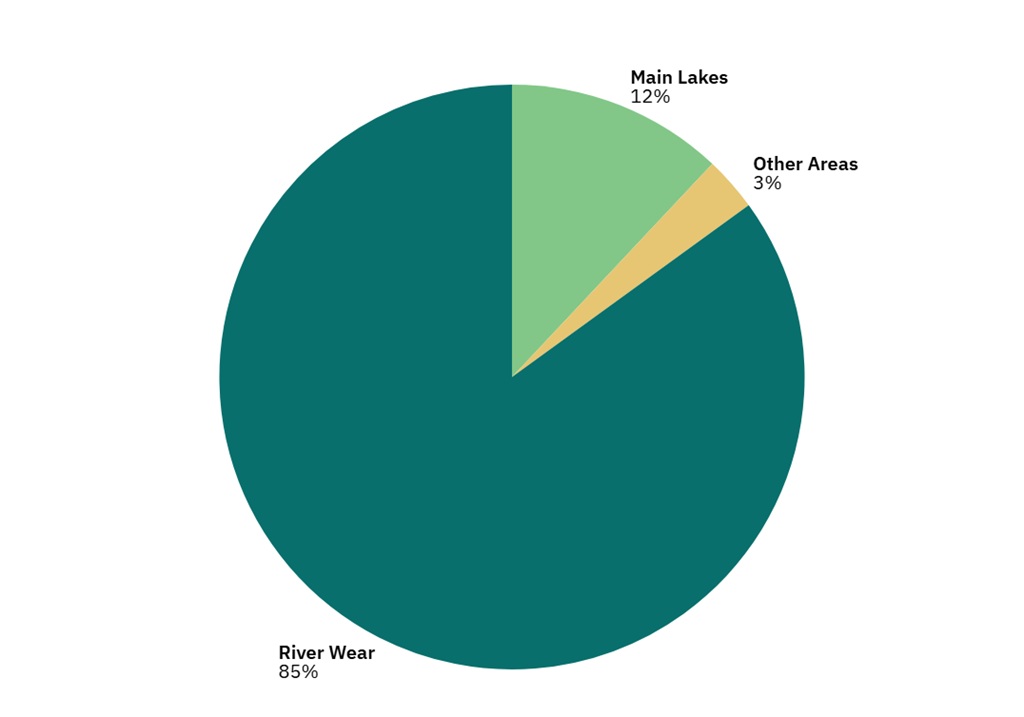

Checking out the pie chart below, which highlights where on site goldeneye were recorded over the last decade, we can see that they strongly favour the river Wear. This means that the best places to spot goldeneye here during the winter are the viewing stations that look out across the Wear at the Dragonfly and Amphibian Ponds, as well as at the other end of Wader Lake near Northumbrian Water hide, where the gully stream enters the river. The “Main Lakes” slice - which makes up 12% of sightings - includes Wader Lake, the saline lagoon and the reservoir, with the majority of those sightings being at Wader Lake.

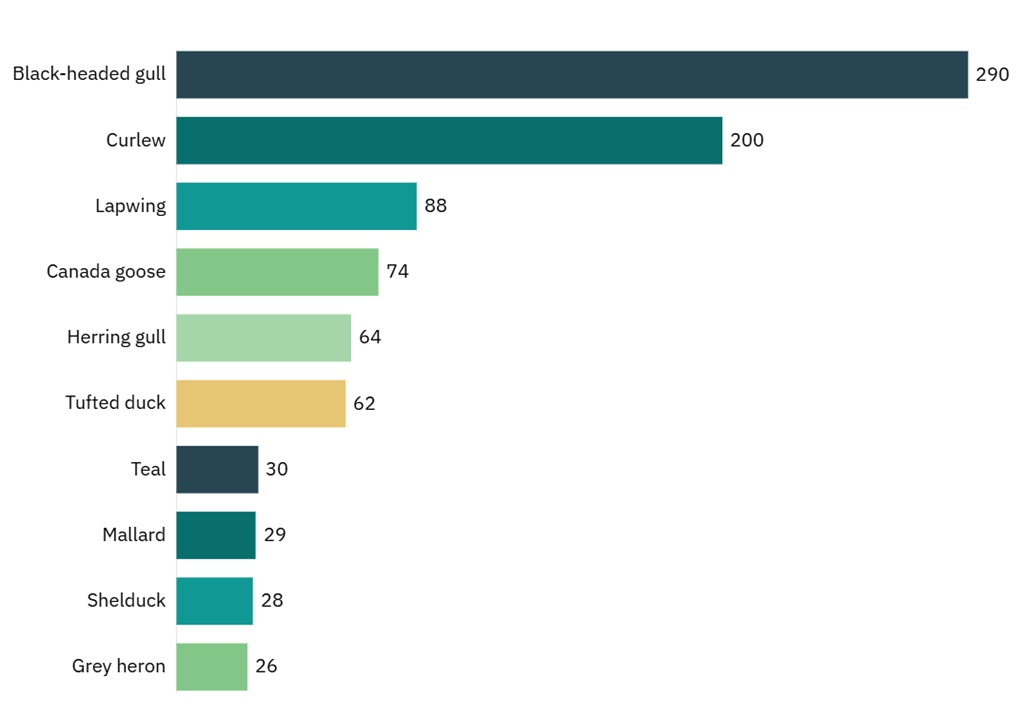

Finally, for a bit of fun, we can take a look at the data from Valentine’s Day (14 February) over the last 10 years and highlight any interesting sightings or observations made. According to the data, we have seen 65 different species of wild birds on this day, the most common being black-headed gull, lapwing and curlew. Taking a look at the graph below we can see the top 10 highest peak counts (most birds seen at one time).

Rarer sightings include single sightings of brambling (2019), goshawk (2018) and treecreeper (2020), as well as the occasional kingfisher, kestrel and little grebe visiting the site across multiple years.

However, given that Valentine’s Day is for the romantic, it feels more fitting to look at couples that have been sighted.

In 2023 a pair of woodcock were spotted in Spring Gill Wood and a pair of willow tit were noted sharing a meal at Hawthorn Wood Hide feeding station back in 2018. Two raven were seen in 2020 at Old Oak Meadow and in 2024, pairs of mute swan, wigeon and oystercatcher were on Wader Lake. Our most frequent Valentine’s Day couple visitors are great-spotted woodpeckers, which have been spotted in pairs on Valentine’s Day for four years in the last decade (2019, 2020, 2022 and 2024).

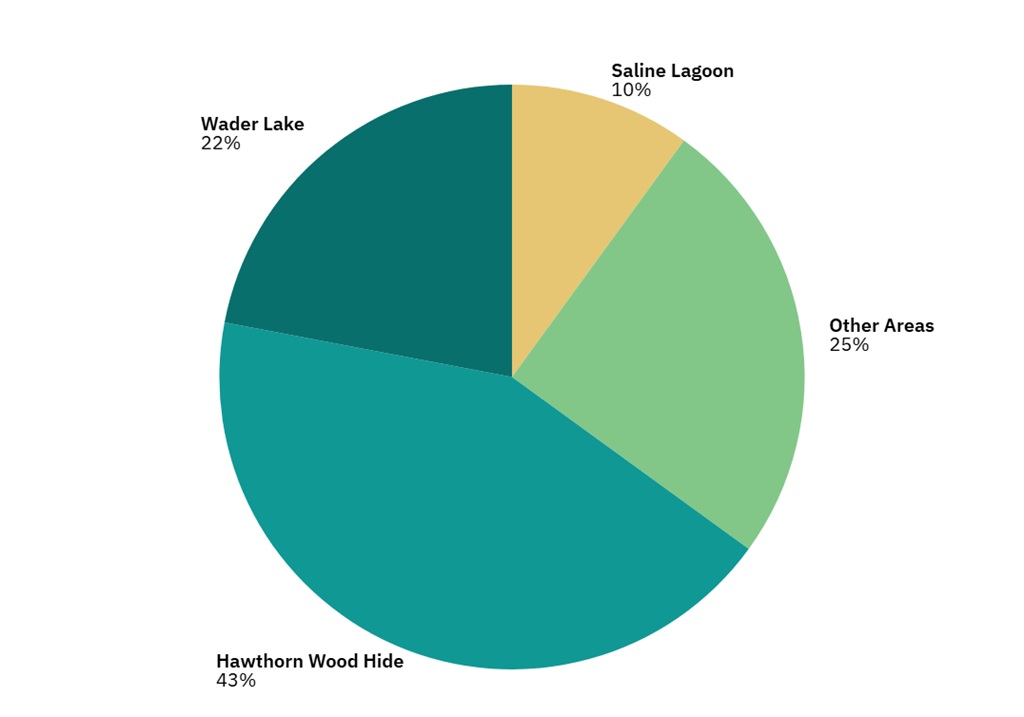

But - according to the birds - where is the best place on site to visit on Valentine’s Day as a couple!?

The pie chart above shows where bird couples were spotted on Valentine’s Day across the last 10 years. Almost half of all visiting couples to the site preferred Hawthorn Wood Hide, probably because of our freshly stocked bird feeders there. “Other Areas” include the river Wear, most of our woodland areas and open meadows (Spring Gill, North Wood, Old Oak Meadow).

This means that the best place, if you’re a bird, for a romantic date on Valentine’s Day, is Hawthorn Wood Hide here at WWT Washington. I think I’ll stick to Waterside Café at the visitor centre for my lunch though!