A biography of Mr James

Everyone's favourite pink bird and one of the stars of WWT's living collection- find out more about our very special (and unique) James' flamingo.

Welcome to summer flamingo fans. There’s been a lot of interest in WWT Slimbridge’s celebrity flamingo of late, our super special Mr James, so I thought it would be a good time to provide an update of his “biography”. All about who he is and where he has come from. Mr James lives in the enclosure with the Andean flamingos and he has been a resident of WWT Slimbridge for many years. Whilst we don’t know his exact age or the year that he was imported into what would have been called “The Wildfowl Trust”, we do know that he is one of our more senior flamingo residents.

Why is he here in the first place?

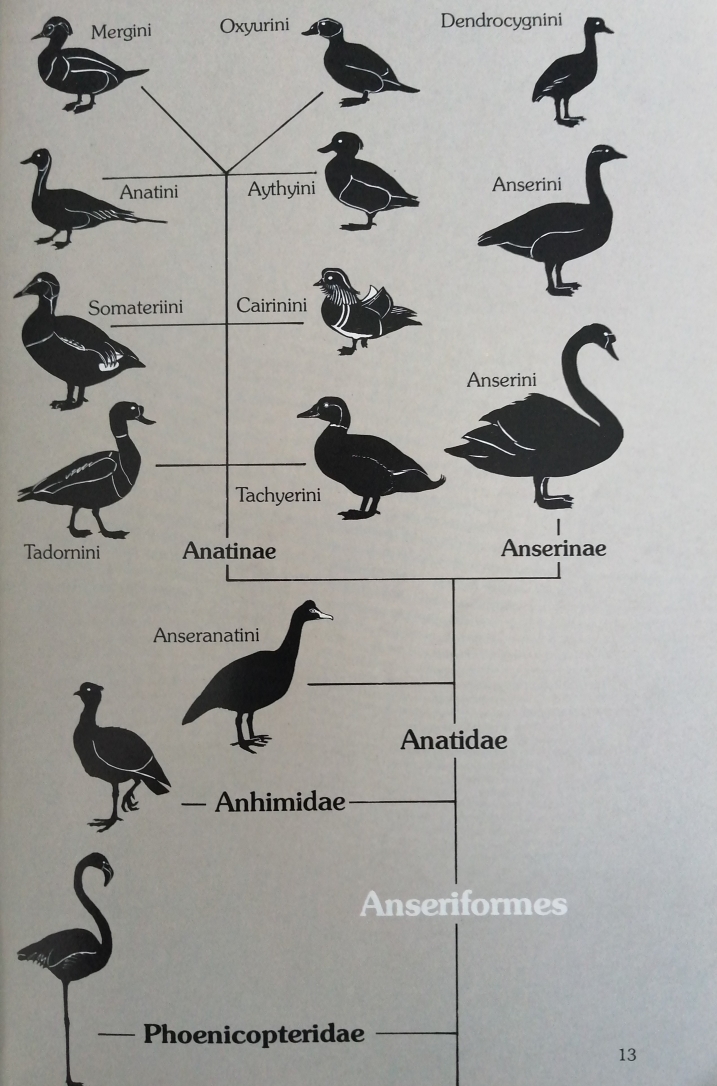

Sir Peter Scott was keen to include all of the flamingo species in his waterfowl collection at Slimbridge. At the time, it was thought that flamingos were closely related to ducks, geese, swans and screamers. Peter Scott drew out a family tree of the wildfowl that included a link to the flamingos, hence the reason why WWT has these birds today. You can see this family tree in the image below, from a guidebook published around 1990 (flamingos appear right at the bottom). We now know that flamingos are more closely related to grebes and wading birds, such as plovers, so this still makes them a good fit into the animal collection at WWT.

The first flamingos arrived at Slimbridge in 1961. James’ flamingos were not obtained until 1965, with three birds being imported. WWT received a few more birds over the '60s and '70s and the flock fluctuated somewhat until 1989 when it became stable at six birds. Records suggest that the maximum number of James' flamingos at Slimbridge at any one time was 18 birds, noted in the 1975 avicultural report. As birds aged over time, we have been left with Mr James.

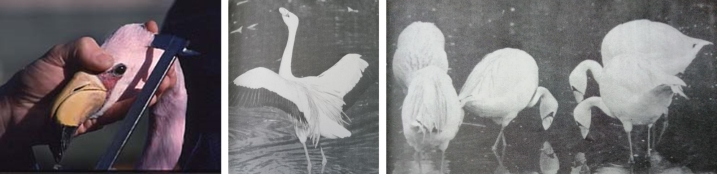

WWT has never bred the James’ flamingo but they have performed their breeding displays, built nests and laid eggs. Mr James’ still goes through the motions of the courtship display and joins in with the Andean flamingos. The photo below shows a pair of James' flamingos building a nest at Slimbridge, probably in the late 1970s or early 1980s (photo by J. Blossom).

The reason for a lack of breeding success is likely to be the need for a bigger flock size (flamingos nest more readily as groups get larger) and the very specialised environmental conditions that this flamingo exists within in the wild. It’s hard to get such a high mountain species to acclimatise to UK conditions, so Mr James is one tough animal.

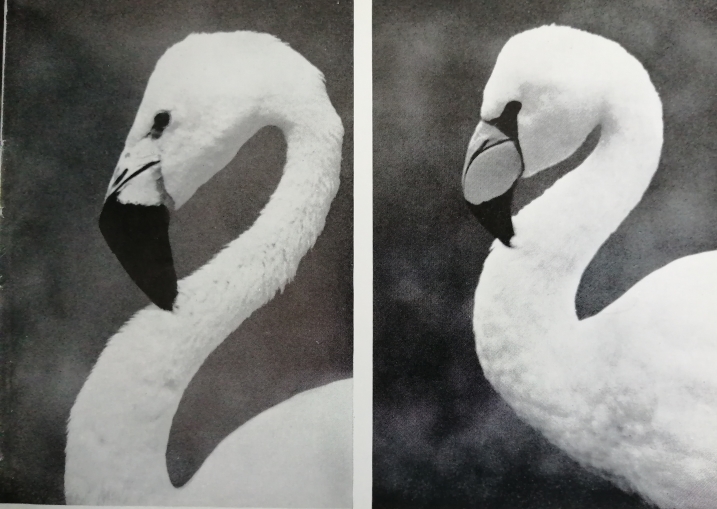

What are the key features of Mr James?

James’ flamingos (Phoenicoparrus jamesi) have distinctive red plumes that droop over their wings, a banana yellow and black bill and orange legs. They have a high-pitched, almost whistling, goose-like call. Their bill is very deeply curved and full of very fine filtering media (lamellae) which is used to collect microscopic algae from the water. In the same genus as the Andean flamingo, James' flamingos feed in a similar way to the lesser flamingo- that also has a very specialised, fine filtering material in its bill (An original article about flamingo beak structure). These three flamingo species are known as deep keeled flamingos, due to the densely packed lamallae in their beaks.

Mr James wears a leg ring with the code JBI.

James' flamingos share an unusual feature with their Andean flamingo relatives- they lack a hind toe. In anatomical terms, this is known as a hallux. Check out the feet of Mr James and you’ll see the difference compared to the greater, lesser, Chilean and Caribbean flamingos.

The name James’ flamingo comes from the naturalist and business Henry Berkeley James who first described the bird around 1886 (and paid for the expedition to collect one). It was thought to have gone extinct shortly afterwards, in the 1920s, but was rediscovered in a remote wetland in Bolivia in 1956. Here's a link to an original painting of this flamingo species- James' flamingo painting.

This flamingo species also has another common name- the puna flamingo The puna is the habitat in South America that Mr James would come from. It shows how important this wetland is to the survival of these flamingos- they are named for a very specific environment that gives them the right conditions to feed and breed in.

A grumpy old man?

Mr James has quite the personality. He is very strong willed and likes to let his bigger Andean flamingo cousins know who is boss. Apparently he has always been a little bit grouchy and didn't really get on with his last James' flamingo friend who died back in 2010. Despite his age, most likely he is in his mid-50s but he could be over 60 years old, Mr James busies himself with what the other flamingos are doing and he likes to make his presence known. If another bird gets in his way or tries to stand where he is standing, then they get to know about it. Slightly grumpy he may be, but we think it adds to his character! You can find him off doing his own thing or hanging out with the rest of the group. Don't be surprised if he's often asleep- he is allowed to take it easy!

Why just one?

We sometimes get asked why is there only one James’ flamingo and isn’t he lonely by himself? James’ flamingos naturally live alongside Andean flamingos in the wild. They share the same feeding and breeding sites, and move between the mountain wetlands of Bolivia, Peru, Chile and Argentina in search of suitable saline lakes that contain the microscopic algae and diatoms (minute floating organic material) that they process to get their bright pink colours. When several species share the same habitat they are called sympatric. Hence it is a natural setting for Mr James to live with Andean flamingos and he regularly joins in with the activities of this flock.

James’ and Andean flamingos are best conserved out in the wild. They are delicate and highly-specialised flamingo species with very specific ecological requirements. Conservation of these species focussed on maintaining the habitats needed for feeding and breeding is the best future course of action for these birds. It’s hard to maintain the number of flamingos in captive flocks to get regular breeding too. So, whilst we will continue to enjoy Andean flamingos (and hopefully Mr James too!) for many more years at Slimbridge we need to put our efforts into keeping these birds safe in the wild, rather than bringing more of them into captivity.

However, it was not a waste to have the James' flamingo at Slimbridge. Mr James and his friends have taught us a lot about the behaviour and biology of this mysterious and relatively unknown species in the six decades they have been at WWT. In fact Mr James still continues to inform and educate. His behaviour has been included in several research papers that document the activity of the Andean flamingo flock. From measurements of the birds themselves, to documentation of their breeding and courtship behaviour, the Slimbridge James' flamingos have added a lot to science and ornithology.

The James’ flamingos in the wild is a Near Threatened species, meaning that it could easily become endangered in the future. The international nature conservation organisation, the IUCN, suggests that the James’ flamingo population is currently stable (IUCN page for the James' flamingo) but because flamingos take a long time to raise young and don’t breed every year this species may be susceptible to a future population decline. It is important that regular monitoring takes place of these wild flocks and community engagement programmes occur to safeguard their future across their range.

WWT is the home of the IUCN’s Flamingo Specialist Group and so Mr James is a great ambassador for flamingos worldwide. Telling their remarkable story of behaviour, evolution and conservation. As one of WWT’s best loved animals, do make sure you go and see him on your next visit.

Mr. James has sadly passed away, read more on the story here.