The pioneering women on the frontline of wetland conservation

It’s not often scientists find themselves in the spotlight, they’re usually working tirelessly behind the scenes. But this International Women’s Day we wanted to shine the light on some of WWT’s leading conservation scientists working to protect wetlands and their wildlife.

Corrie Grafton

Corrie manages one of WWT’s key Natural Flood Management projects. The project supports local authorities to deliver NFM in high flood risk areas.

My job is to support communities and local authorities to put NFM into practice in their areas. Previous work I’ve done has shown me the amazing benefits that nature-based solutions deliver. I believe it’s essential they’re integrated into strategy and policy to increase climate resilience. My work showcases the multiple benefits that nature-based solutions provide and helps to raise the profile of this work.

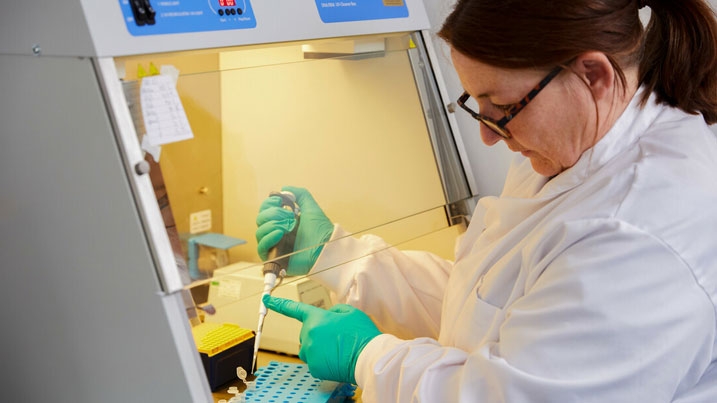

Abigail Mackay

Abigail is a researcher in the Wetland Science Team specialising in environmental DNA (eDNA) surveys.

I’m interested in all the ways we can use genetics in conservation, so the main focus of my work is on eDNA surveys. I analyse water samples for DNA from specific species - such as eels - to help us better understand which environments these species choose to live in and why. This in turn helps us to support endangered species, like the European eel, to thrive again.

Hannah Robson

Hannah’s team provides the scientific evidence that underpins WWT’s conservation work on the ground.

I manage WWT’s Wetland Science laboratory. We carry out lots of different types of analysis that provides data to support WWT’s conservation work. One of the most fascinating techniques we use is collecting sediment cores (basically tubes of mud that we extract vertically from the floor of a lake or pond). It’s like a timeline of events, each year's sediments (and remains of the creatures living in or around the wetland) are preserved and stacked on top of the ones from the year before. We’re using this technique across lots of projects to shed light on how water quality, biodiversity and carbon storage have changed over time, and to help us identify the best way to restore wetlands.

Sarah Davies

Sarah is part of a team highlighting the value of farmland ponds for biodiversity.

Currently my work is focused on providing evidence of the multiple benefits of farm ponds. Ponds support more rare species than any other freshwater habitat, and research shows clear links between their management and thriving populations of farmland birds. We’re pioneering a technique called pond labelling. We add tiny amounts of a non-toxic isotopic label to the pond, which is taken up by plants, algae and aquatic insects. It helps us to understand how ponds boost biodiversity by providing food for birds as well as amphibians and other animals. In time we’ll also be able to analyse droppings to see which animals are benefiting from ponds and how far they’ve travelled to get there.

Laura Weldon

Laura leads research into biodiversity changes that occur when Natural Flood Management interventions are introduced.

I deliver the scientific data to quantify changes to biodiversity when Natural Flood Management is used as a solution to flooding in rural communities. By monitoring the effects these small changes have on local biodiversity, we provide evidence of the additional positive impacts we gain from using natural solutions. In turn this provides incentive to communities and local authorities to support the use of more natural interventions for flood prevention.

Sue Kinsey

Sue is WWT’s engagement officer for the Flourishing Floodplains project. She runs community workshops to inspire and engage people in local wetland nature.

My job is about spreading the word on the brilliance of wetlands. I speak to local communities about how amazing our floodplains are, encouraging them to support their local wetlands in any way they can. Not only for their beauty, but also because they can help to prevent flooding, are vital for pollinators and the animals that depend on them and can improve water and soil quality.